Read the whole blog on CCIRA here.

This spring, we were kidwatching during Independent Reading in a first grade classroom. A boy with a huge pile of books in front of him beckoned us over. “Listen to me read!” he said gleefully. He read book after book, pointing out all the funny parts. “I’m a good reader!” he proclaimed.

Later, his teacher confided in us, “I’m worried that no one will recognize his growth. No one will know how he felt about himself as a reader in September and compare it to how he feels about himself now. They won’t see the joy that reading brings him or how he sees it as part of his life now, when in September he only occasionally picked up a book. They will just see his level on the test and label him as a struggling reader.”

This encapsulates the ongoing contradiction between how reading growth is traditionally measured and defined by tests, and what teachers observe and experience to be a more complete concept of reading growth. Current policy and testing practices continue to reinforce the misconception that student reading growth encompasses solely the accumulation of skills and strategies (Afflerbach, 2022), thereby reducing the definition of what constitutes reading growth. However, both the experience of teachers and an overwhelming amount of research tell us reading is more complex than that. What constitutes reading growth and how it is measured needs to better reflect this complexity (ILA, 2018), expanding to include aspects of reading such as engagement, motivation and self-efficacy.

What we see as growth, and what students feel is growth is disconnected from what is officially recognized as growth. At the end of the school year, reading growth is too often reduced to a grade on the report card or a number or letter, or is defined by a set of discrete skills that can be measured by standardized tests. These measures do not capture the joy or the nuances of being a reader.

What data counts?

Data promises to inform and support the work of teachers, and yet data has become a burden. In reality, many teachers are drowning in data, and not the sort of data they find useful. Typically, the data teachers are directed to utilize is confined to big data such as standardized tests, universal screeners or benchmark data. That sort of data is often used to tell a story of “learning loss” or name who is “below grade level.” A recent Hechinger report (February, 2022) asked “… has all that time teachers spent studying data helped students learn? The emerging answer from education researchers is no.” This comes as no surprise to educators themselves. The big data that is valued by the system is not the data that supports the work of teachers in classrooms in meaningful ways, yet it tends to dominate our time, our definitions of achievement, and the stories told about our students and our work.

An over reliance on this big data runs the risk of narrowing the vision of the role of the teacher. When framed by deficit-minded data, the teacher turns into someone who fills gaps and catches students up to the benchmarks that indicate grade level proficiency.

Our role is to teach responsively, not to “fill gaps.” Our role is to be asset-minded. Our role is to assume a stance of non-judgemental relentlessness in the pursuit of growing readers. Our role is to uncover student strengths and provide relevant feedback that will build upon those strengths. Our role is to center students. In our hearts, we know that big data often limits our role as teachers of readers and does not tell the whole story of our students. When small data, such as kidwatching or conferring notes, is valued, we are suddenly presented with a more nuanced portrait of growth that indicates relevant next steps for each student.

Navigating the Contradiction

We urge teachers to harness their sense of agency and take control of the narrative by expanding the definition of reading growth to tell an authentic story of progress. Maxine Greene, the great educational philosopher, believes that teachers have an obligation to choose to engage with struggle, such as the contradiction discussed above. She states that by engaging in these struggles, rather than giving in to one side or the other, teachers can move toward a state of “wide awakeness” that welcomes the creativity and agency necessary to humanize and transform possibilities in education. In Releasing the Imagination (1995), she writes, “…to learn and to teach, one must have an awareness of leaving something behind while reaching toward something new, and this kind of awareness must be linked to imagination.” How can we navigate this contradiction and imagine new spaces of possibility for our students and ourselves?

Here are some practical ways to navigate this contradiction:

- Prioritize Independent Reading and the Read Aloud

Both Independent Reading and the read aloud are research-backed literacy practices that satisfy standards while meeting students where they are. Independent Reading time has the potential to develop reading comprehension ability, vocabulary, grammar and spelling (Krashen, 2004), spark actions for a more just world, (German, 2021), improve reading fluency (Allington, 2014) … and the list of advantages goes on and on. Every student has the right to Independent Reading; it is not an add-on or a luxury. Similarly, the read aloud is an enjoyable and impactful time of day. Effective read-alouds increase children’s vocabulary, listening comprehension, story schema, background knowledge, word recognition skills, and cognitive development. (ILA, 2018).

During Independent Reading and the read aloud, teachers have the opportunity to engage in intentional kidwatching, to notice and name the strengths of students as readers, and to begin to build a broad understanding of reading growth for each child across the school year. During Independent Reading and the read aloud, students have the opportunity to be their authentic reading selves.

- Honor, consider and follow the growth of the identity of each reader

On this blog in March of 2021, we shared our definition of reading identity (Reflection and Discovery: The Power of Reading Identity in Independent Reading ) We define reading identity as having five aspects: attitude, self-efficacy, habits, book choice and process. If we use these aspects as a jumping off point for imagining what reading growth means, then reading growth becomes authentic and includes much more than a grade. Reading growth can (and should) include:

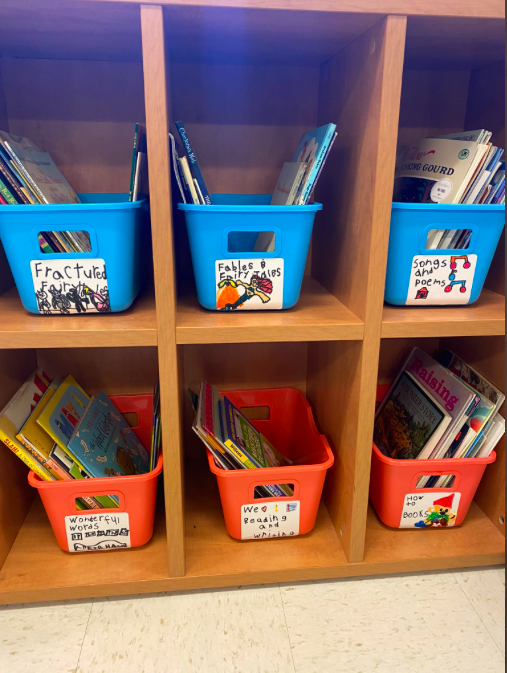

- Choosing different genres

- Reading for longer periods of time

- Having favorite books

- Using a variety of strategies to decode words independently

- Holding on to multiple plot lines and characters

- Comparing and contrasting genres and books

- Responding to texts in a variety of ways

- Wanting to read

- Knowing book preferences

- Declaring: “I am a reader.”

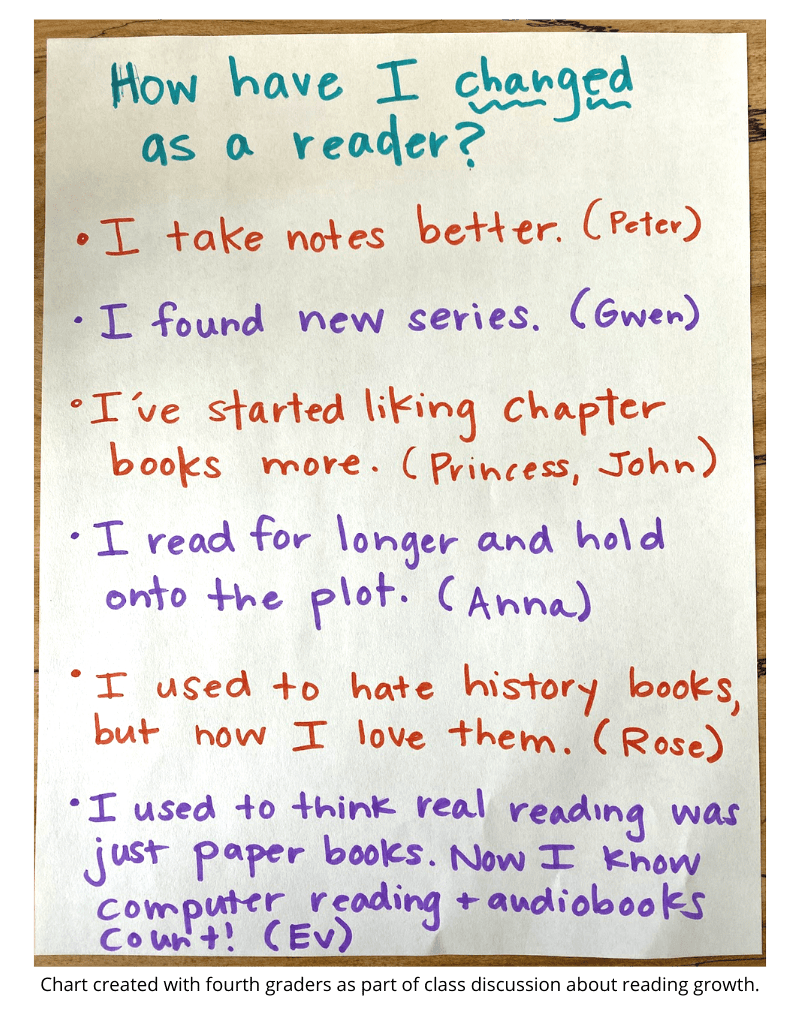

As you confer with students during Independent Reading, provide feedback on what you observe about their growth. Invite students in class discussions to reflect on how they have grown as readers. Ask: “What are the ways in which you have changed as a reader? What made you change?” Encourage students to tell stories about themselves as readers and how their reading life has developed.

- Reclaim Your Role

Regie Routman (2003) writes that “teaching with urgency means focusing relentlessly on what is most important every single day.” Therefore, teaching with urgency means to teach responsively, to start with student strengths and to provide relevant feedback that build upon those strengths with clear next steps. Students are what is most important every single day. It is through the lens of deep understanding of our students as readers and learners, that we must approach curriculum, assessment and methods of instruction. To put students at the center, teachers must continuously reflect on the impact of their decisions, the curriculum and assessment opportunities. It also means that as a result of this reflection, teachers feel a sense of agency to not only embrace and expand upon what is working, but to give themselves the grace to let go of those practices, routines or tasks that no longer invite positive or productive outcomes for students.

In one classroom, a veteran fourth-grade teacher chose to abandon a read aloud text that had worked for years, because it no longer captured the attention of her class. Instead, she presented the class with a variety of possible texts that fit the genre and purpose of her current instruction; when the students were involved in picking the read aloud, their engagement in class discussions soared. In another classroom, a teacher realized that she never got to the read aloud, because it was at the end of the day. She changed the schedule so that she started the day with the read aloud. Students were actively involved in class conversations, and the read aloud became a jumping off point of instruction.

- Trust Small Data and Broaden the Definition of Reading Growth

We know that big data does not tell the whole story. Instead, big data measures such as state tests might show that students are “behind” or “at mastery” or “meet the standard.”

In contrast, small data, such as kidwatching notes, presents a more nuanced portrait of growth and indicates relevant next steps for each student. It provides actionable, in-the-moment data upon which teachers can take action. Take charge of how time in data-focused meetings is spent. Shift team meetings to include analysis of small data; focus on naming strengths, and the natural next steps that build upon those strengths. In tandem, these two moves can shift both the instructional and emotional climate to embrace a narrative of progress that is beneficial to the morale and growth of students and educators alike.

Final Thoughts

So how are you going to move forward? We urge you to focus on and imagine what could be, rather than feeling weighed down by what is, because imagining and expanding upon what reading growth can and should encompass is a step toward reclaiming a narrative of progress.

We urge you to take the brave step of moving away from limited definitions of growth and advocating for all that counts when we consider the authentic reading lives of students in and beyond school. For teachers, a wider stance allows us the ability to center students and focus on teaching readers, not just reading. For students, this wider stance honors their authentic reading lives, their whole reading identities and their everyday reading successes.

As your school year comes to a close, know that your observations of students and students’ reflections count as data. Encouraging your students to believe in themselves as readers, and supporting students to understand their identities as readers counts as growth. Broadening your students’ repertoire of strategies counts as growth. Nurturing your students’ sense of trust that they are and will continue to be readers counts as growth. It all counts.

Dr. Jennifer Scoggin has been a teacher, author, speaker, curriculum writer, and literacy consultant. Jennifer’s interest in the evolving identities of both students and teachers and her growing obsession with children’s literature led her to and informs her work.

Hannah Schneewind has been a teacher, staff developer, curriculum writer, keynote speaker and national literacy consultant. She brings with her over 25 years of experience to the education world. Hannah’s interest in student and teacher agency and her belief in the power of books informs her work with schools.

Together, Jen and Hannah are the authors of Trusting Readers: Powerful Practices for Independent Reading, published by Heinemann. They are the co-creators of Trusting Readers (@TrustingReaders), a group dedicated to collaborating with teachers to design high quality literacy opportunities that invite all students to be engaged and to thrive as readers and writers.

Works Cited:

Afflerbach, Peter. 2022. Teaching Readers (Not Reading): Moving Beyond Skill and Strategies to Reader-Focused Instruction. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Allington, Richard L. 2014. “How Reading Volume Affects Both Reading Fluency and Reading Achievement.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 7 (1):95-104. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1053794.pdf.

German, Lorena. 2021. Textured Reading: A Framework for Culturally Sustaining Practices. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Greene, Maxine. 1995. Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hechinger Report. 2022. Proof Points: Researchers blast data analysis for teachers to help students. New York, NY: https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-researchers-blast-data-analysis-for-teachers-to-help-students

International Literacy Association (ILA). 2018. Literacy Leadership Brief: The Power andPromise of Read-Alouds and Independent Reading. No. 9445. Newark, DE https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/where-we-stand/ila-power. promise-read-alouds-independent-reading.pdf.

Krashen, Stephen. 2004. The Power of Reading: Insights from the Research.Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Routman, Regie. 2003. Reading Essentials: The specifics you need to teach reading well. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.